|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2015 was the the 200th Anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, This page is dedicated to the memory of a brave Blidworth Lad, Matthew Clay 1796 - 1873: Read on.

From humble Private Clay at the Battle of Waterloo, to

Sergeant Major Clay of the Bedfordshire Militia.

The writer’s great, great,

great-grandfather, Thomas Clay, was born on 31 July 1803 in Blidworth and baptised

at St Mary’s Church. His father, Mathew Clay and his mother, Sarah Gilbert, had

married on 5 January 1781 at St Mary’s. Their eldest son was Matthew, who was

born on 6 March 1796.

Matthew started work when he

was 11 or 12 as an apprentice framework knitter as this was an important trade

in Blidworth at the time. He worked at this for seven years before joining the

army at the age of 18. He enlisted in the Third Regiment of Foot Guard, the

Third Scots Fusiliers Regiment, in London on the 6th December 1813.

He was 5 foot 7 inches tall with a fresh complexion, grey eyes and light

coloured hair. Possibly because of his lack of height he served first with the

2nd Battalion commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Master in Holland and

France from 1814 until 1816. He was captured and imprisoned but only for a

couple of weeks, being set free as Paris was liberated. When in France he

started writing a pocket account book, which is now held by the Bedfordshire

and Luton Archives Service (Ref Z1081). The writer purchased a copy in 2009 for

£120.

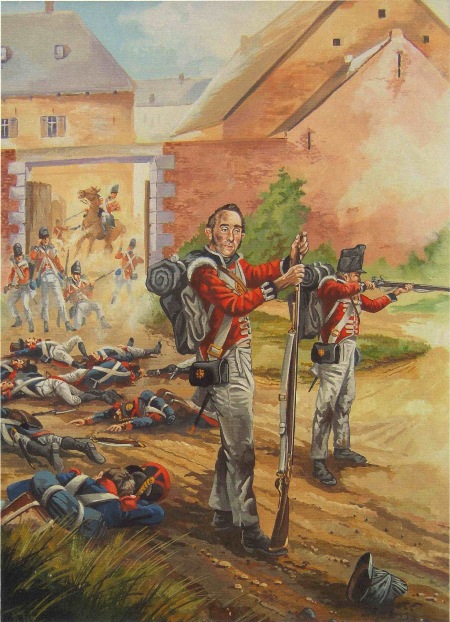

His story starts on the morning

of 16th June 1815 at Quatre-Bras and he writes how he was fighting

in the battle that day, quickly reloading his musket. By evening, as the

battalion settles down for the night, he goes to look for water as he remembers

passing a stream just before it got dark. He soon finds it, fills his kettle

and takes it back for his friends and the injured. As he drank from it he

thought it had a funny taste but it was still refreshing. Just as it was getting

light he went for some more but when he looked down at the water it was red

with blood; dead bodies were everywhere, so he did not refill his kettle but

hurried back as the battle had started up again.

After fighting at Qutre-Bras

the battalion headed to the Chateau at Hougoumont through the crop fields where

he fell into a puddle up to his neck as they had had a lot of rain the night

before. It was another day of fierce fighting and his musket kept misfiring, so

he found one on a dead body which was dry so it was ‘load and shoot’ all day.

That evening the soldiers lit fires to dry their clothes and warm themselves.

The sergeant came round giving them all a piece of bread, ‘about on ounce’.

They were near the farmyard now so one of the troopers caught and killed a pig.

Matthew’s portion was a part of the head!

It started to get light and the fighting had started again in the

direction of Hougoumont Farmhouse and that is where they headed, dodging cannon

fire and bullets. Matthew wrote, ‘I was quite a target in my red coat, being

more distinctly viable than theirs, ‘The French.’ He saw the lower gates of the

Chateau were open and soldiers were lying dead and injured. When they got

inside Lieutenant-Colonel Dashwood and captain Evelyn of the same company, were

there wounded. The battle was full on. At the gates of Hougoumont they were

climbing over the dead bodies, injured French and their own men too. He saw

Colonel McDonnell carrying a piece of wood or a trunk of a tree in his arms,

with which he used to secure the gates against the renewed attack of the enemy.

This action probably saved the day as historians are agreed that the defenders

of Hougoumont decisively affected the outcome of the Battle of Waterloo. The

book that Matthew wrote has fantastic accounts of the war and it makes you feel

as if you are with him as you read it. *

Lance Sergeant Gorman of the

Scots Guards Archives has said,

‘Of all the narratives that

have been written concerning that most ‘memorable battle of waterloo’, Matthew

Clay’s account is one of the most vividly described. It provides the reader

with a ‘soldier on the ground account’ of battle during the Napoleonic period.

His account has been used worldwide by authors and is considered one of the

rarest Private Soldiers account of not only Waterloo but of the battle for

Hougomont Farm, which if it had not been defended so bravely and so well,

Waterloo may have been a French Victory and Europe may well have been a very

different place from what it is today!’

Matthew Clay returned home with his battalion and had a more

settled family life. He was promoted to Corporal on 21st march 1818

and then he became the 1st Pay and Drill Sergeant of the Scots

Fusilier Guards on 14th February 1822. He did serve abroad again during the Carlist Wars** when the

Battalion was sent to Portugal between 2nd January 1827 and 15th

April 1828.

Matthew married Johanna on 27th

February 1823 at Stoke Dameral in Devon. They had twelve children but only a

few survived infancy. His youngest son tragically committed suicide in Kirkee,

India. Albert was born in 1840 in Bedford and followed his father into the Army

until he retired. He and his wife had nine children. One was Charles Alfred

Clay, which was the writer’s father’s name. His other son, also a Charles, born

in 1839, married and spent most of his life in Canterbury as a Railway

signalman.

Matthew was a gymnast and an

athlete, having been a Drill Sergeant in the Guards for eleven years. He taught

drill to the Duke of Cambridge, the Marquess of Abercon and other distinguished

gentleman. He was held in the highest respect by the towns people of Bedford

and also his family and friends in Blidworth. Matthew was fortunate never to

have been wounded and was eventually discharged from the service at his own request

in 1833 when he became Sergeant Major of the Bedfordshire Militia, a rank he

held until 1852.

Matthew struggled to make ends

meet a few years before he died. The old veteran had denied himself necessities

to keep his ailing wife, Johanna, alive without asking for charity. He had to

sell his possessions so that he could pay the rent. His plight was eventually

discovered by a General Codrington whose letters to The Times started a fund for the Sergeant, which soon grew

to £100. Unfortunately, the last enemy was too strong and Matthew died on the 5th

June 1873 aged 78, before he could benefit from the General’s kindness. He died

a pauper but was given a hero’s funeral and thousands of people came to pay

their respects. On the top of his coffin lay his sword and a ring of laurel

leaves, because when he was alive, on the anniversary of the Battle of

Waterloo, he wore a sprig of laurel leaves to remember that day. He must have

worn them with great pride.

Lance Sergeant Gorman believes

that if it had been available at the time, Matthew Clay would have awarded the

Victoria Cross; the highest honour that a soldier can be awarded.

* ‘A narrative of the battles Quatre-Bras and Waterloo’

by Matthew Clay, Bedford. Reprinted 2006 by Ken Trotman Publishing, Ed. Gareth

Glover, ISBN 1905074255.

** Early Spanish civil war.

The writer is Christine Dabbs Clay who has found

that her ancestors have lived in Blidworth since 1675. Many were baptised,

married and buried at St. Mary’s Church in Blidworth.